Mind the (Emissions) Gap – 2024

The 2024 Emissions Gap Report from UNEP.

In brief –

The United Nations Environmental Protection agency (UNEP) annual Emissions Gap Report 2024 has recently been published and it is probably no surprise it is not a particularly comforting read although there is room for some hope, as ever if the commitment to take the necessary actions can be summoned up. The core message is that unless the scale of emission reduction commitment and action are significantly increased then it will be come near impossible to reach our climate safe goals to limit planetary heating – the report calls it a ‘a quantum leap’ in ambition combined with ‘accelerated action‘ in the 5 remaining years of this decade.

Context –

The report charts the gap between national emission reduction commitments and the emissions budget limits to keep global average temperatures within safe boundaries of 1.5 degree or 2 degrees warming.

It analyses the gap in terms of current levels of CO2 emissions and current emission reduction policies in operation as well as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) which are the commitments that countries make under the Paris Agreement process to limit dangerous global heating.

These NDCs are required under the Paris Agreement to be updated on a regular basis (every 5 years minimum) and include ‘unconditional‘ elements which a country gives an absolute commitment to undertake as well as a ‘conditional‘ commitment elements which are dependent on other things occurring first. Often for developing countries this means various forms of assistance from developed countries in line with the common but differentiated formula in the Paris Agreement that recognises the large differences in capacity and indeed responsibilities to reduce carbon emissions).

There is a further new form of commitment which the Gap Report also covers related to ‘Net Zero Commitments‘ where over 100 countries, representing 82% of all GHG emissions have adopted pledges to reduce their emissions to net zero, typically but not in all cases by 2050, ( where any residual GHG emissions are offset by nature based and human led carbon removal and storage). The Net Zero Commitments often represents the highest level of national commitment but as the report points out, the strength of such commitments are too often dogged by a lack of legal status, lack of serious implementation plans or any alignment of short term actions with the pathways required to achieve this longer term ambition, particularly taking into account the enormous level of transition that is required in countries production and consumption. It is easy to look good by making promises that someone else will have to deliver at some future time but making it all the harder to do so then for failure to properly prepare for now.

Key Findings –

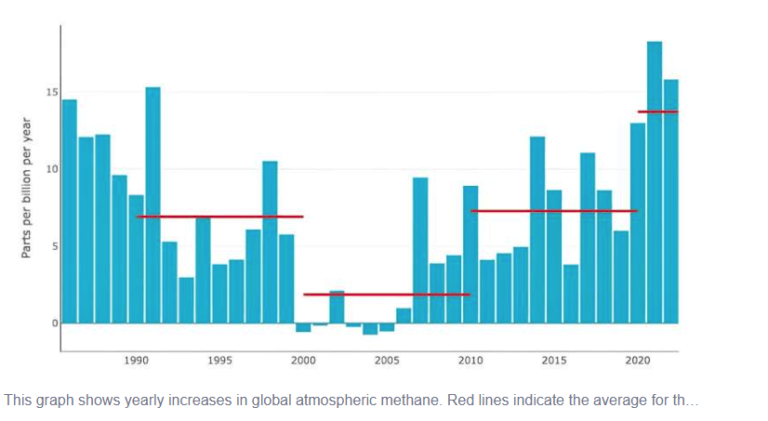

Emissions reached 57.1 GtCO2e in 2023

The ‘e’ stands for ‘equivalent’ which converts all other types of GHG emissions, such as methane, to the CO2 equivalent heating potential and combines them to a common total. This represents an increase of 1.3% on total 2022 figures and occurred across all sectors except for land use. The break down of emissions by sectors is:

15.1Gt (26%) for electricity power,

8.4Gtn (15%) for transportation,

6.5Gt (11%) industry

6.5Gt (11%) for Agriculture

and after fuel production accounts for 10%, industrial processes account for 9% and land use change 7%.

The emissions gap has not changed since 2023.

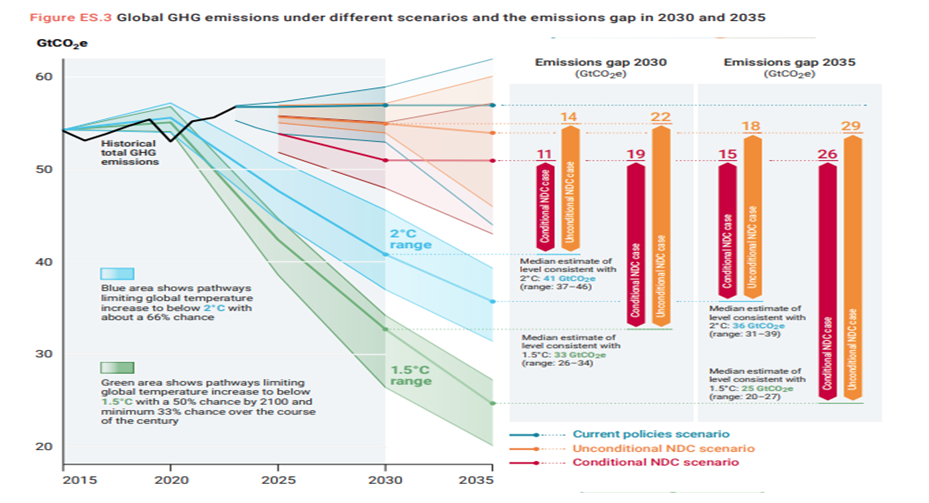

The current NDCs of all countries together commits us unconditionally to a reduction of just 2 GtCO2e by 2030 and 6 GtCO2e for conditional NDC commitments.

A median carbon budget level of 33GtCO2e emissions is required by 2030 to keep within 1.5 degrees of heating meaning a gap of 22 GtCO2e or 42% of total annual emissions exists for unconditional commitments (a gap of 19Gt for conditional commitments) by 2030.

To keep within 2 degrees, the reduction required is 14 GtCO2 or 28 % reduction for unconditional commitments (11Gt for conditional commitments). Still a massive challenge bearing in mind this is only 6 years away to 2030 and emissions are still rising. But a 2 degree rise compared to 1.5 degrees come with significantly increased exposure to climate harm and potential tipping points for the slippage.

Lost Time:

The total remaining carbon budget in 2024 for a +1.5 degree world has reduced to 200 GtCO2e and 900 GtCO2 for a +2 degree world.

At current emission levels it is perhaps not surprising that more and more scientists are doubting the feasibility of remaining under 1.5 degrees warming. But as the report also points out, the world is in fact 2 steps off track; firstly in terms of total emission reduction commitments, compared to temperature goals (either 1.5 or 2 degrees) and secondly because we are falling short on the reductions we have already committed to. The report estimates this delivery shortfall already to be in the order of 1Gt CO2 off ( ie. projections current policy exceeding NDC projections) .

Seven of the G20 countries have yet to peak in terms of growing emissions whilst 10 have peaked in terms of total emissions. Achievement of the emission goals will depend on speed at which they peak and the rates of decarbonisation respectively. Further delay will result in ‘unfeasibly rapid decarbonisation later’. This puts the focus squarely on the transition efforts and promises in NDCs revealed at COP29 in November 2024 and at COP30 in 2025. COP29 as seen was a big disappointment

current Commitments makes some difference (even if not enough) –

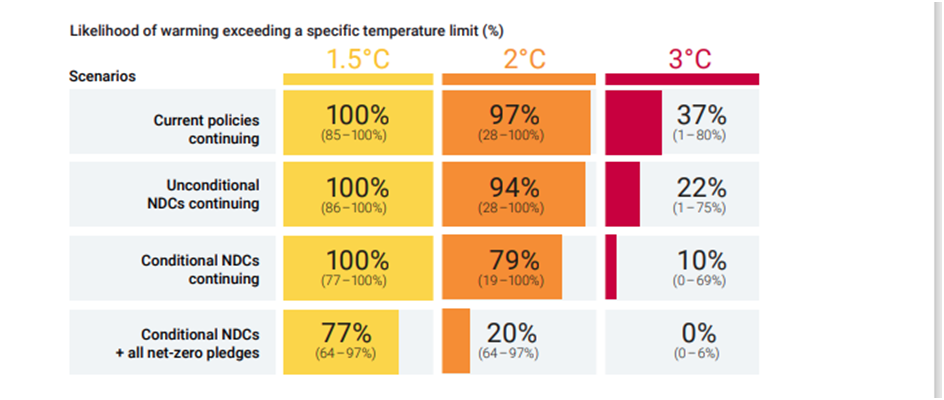

Continuing with current policy only, the report indicates results in warming of 3.1C above pre-industrial temperatures over the next 70 years (which considered in the context would result in quiet devastating consequences and high potentials for cascading impacts and potential run-away heating).

Unconditional NDCs reduces the projected heat rise to 2.8C rise and conditional NDCs to 2.6C; so assuming implementation this means 0.5 degree reduction in heating from business as usual current policies; already a meaningful and significant reduction. However it also means virtual certainty of losing not only the 1.5 degree goal but also the 2 degree goal.

It is only if the stretch ambitions of Net Zero Commitments, as currently stated that there is any reasonable possibility of reducing to a 1.5 degree warming world which is estimated in the report at 1.9 degrees Centigrade. The diagram below illustrates the likelihood of warming exceeding stated temperature goals under the different levels of reduction commitments makes for sobering reading:

But real hope (and challenge) lie in energy sector speed of transformation.

While the report condemns as woefully short the progress towards benchmarks in key sectors to bring the world back to a 1.5 degree heating limit, but sees some potential to do this if relevant policies, finance and support can be massively boosted.

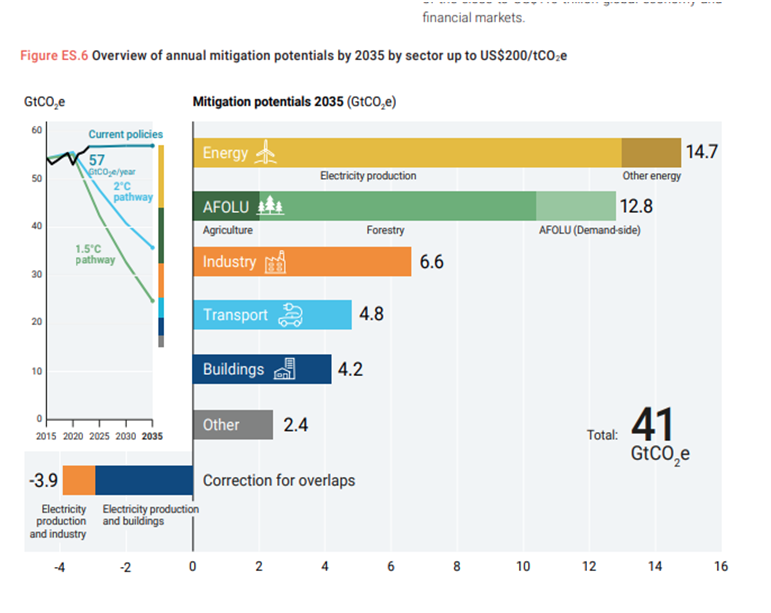

Estimating the cost in the region of $200 per tonne CO2e; the report identifies potential of closing the gap and reducing emissions by 31 GtCO2e by 2030 and by 41GtCO2 by 2035.

Increased rate of electricity power transformation to clean sources can make a full 27% of this reduction by 2030 while agriculture and forestry related action contributes 19% of this potential for reduction by 2030. Central opportunities for transformation of energy systems to achieve these potentials, arise in energy efficiency (‘energy not used is the cleanest energy’) and other measures to reduce total energy demand, electrification of energy systems as well as clean sources of power and fuel switching in transport (to electric vehicles), buildings and in industry. All these should be central policy objectives of all climate conscious governments but ultimately that will only happen with the public support and demand for these measures as they are neither cheap nor easy to deliver.

Costs of this step change in Energy Transformation –

This increased transformation effort is estimated will cost 6 times current mitigation investments and the shifting of investment to developing countries where emissions are significantly growing due to the massively growing demand for power. Considering for example, that India has similar population size to China but only approximately 1/3 the size of its power and emissions, it is essential that India and other developing countries future development pathway is a clean one.

The report estimates the increased cost of this clean energy transition at between $0.9 and 2.1 trillion per year but puts this in context of a global economy valued at $110 trillion.

This also puts in context the demand from developing countries at the recent COP29 for support of $1.3 trillion per year. But in a worrying potential indication of the future directions, the final figure agreed at COP29 whilst it did treble the current commitment to $300 billion dollars, it is still substantially below what is required to fund the scale of transformations required. Again, it is only a full understanding of what we are facing in terms of the Climate Crisis as well as an appreciation of the needs of developing countries in terms of financial support that will prompt the necessary response. This can be significantly influenced by engagement and demand for these actions from climate action supporters.