COP29 – Disappointment in Bacu

Conference of the Parties (COP) 29 in Bacu, Azerbeijan ends with poor results

Gloom descends

Towards the end of November 2024 and just after the US elections returned Donald Trump to the White House, the 29th Conference of the Parties hosting all countries of the world to work towards the Paris Agreement goals under the UNFCCC framework concluded in Bacu under presidency of Azerbeijan after two weeks of negotiation. So what did it achieve? Well the short answer is not very much at all compared to what was called for and very short of what was needed. Carbon Brief has provided a comprehensive outline of the negotiations and outcomes over which it can fairly be said that the shadow of election of Trump had a chilling effect on the willingness of the parties to offer and agree. In view of his support for fossil fuels and indication that he would take the US out of the UNFCCC and COP global climate engagement processes on his return to office, as he did the first time round.

Not least responsible for that result was the COP presidency of Azerbaijan which , for a third year in a row, is a ‘petro-state (dependent as Carbon Brief reports on fossil fuels for 90% of its exports). So none too keen to promote the demise of fossil fuels, or even to allow debate on the transition away. The outcomes prompted a former UN climate chief, Christine Figueres to sign an open letter that the COP process was ‘no longer fit for purpose’ before rowing back in realisation that ’ it is the only forum the world as a whole has to come together to find solutions‘. That is of course both its strength and its weakness as the global consensus based process can so easily result in no or weak agreement, a case of the lowest common denominator too often, sadly.

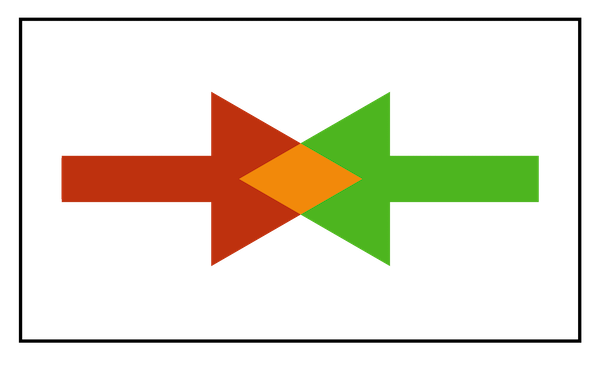

Transition from Fossil Fuels

The problems started from the start with a big fight over what should actually be on the COP agenda and specifically the ‘stocktake’ outcomes from the COP28; which are meant to reflect on progress and which made the landmark call to contribute ‘to transitioning away from fuels’ as well as pledges which aligned with the 1.5C limit.

But Saudi Arabia, predictably, rejected any mention stating the Arab Group would not accept any text that targets any specific sector; conveniently in this way brushing aside consideration of the fossil fuel sector; the sector directly responsible for 75% of all green house emissions and 90% of all carbon emissions.

Climate Finance

Having safely batted away the risk of the stocktake making a meaningful contribution to the discussions, the focus turned to focus turned to climate finance, which as noted in the WEO 2024 report is a critical component for developing countries to transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

Developing Countries called for developed countries to contribute $1.5 trillion in the form of direct grants from public sources. In the end, the decision called on all parties, including developing countries, to merely make a financial contribution to the New Climate Finance goal (NCQG), to be made up of private as well as public funds; loans and grants. This could include repayable loans as well as other funding sources. So the final commitment was much weaker than the original demand for publicly sourced grant funding.

But it was the size of the new NCQC funding instrument that the most wrangling and ultimate disappointment was felt . No figure was indicated until the last days and then offered a fraction of the original amount requested at $250 billion per year from 2035 (safely a full ten years away with inflation having depleted that value considerably by then).

To put this in context, the actual cost of transition for developing countries is estimated at $2 trillion annually by 2030 by the IMF with a majority of that money required for energy transition. China and G77 group of countries were content with a figure of $500 billion. The final figure agreed was $300 billion, from all sources with voluntary contributions from developing countries ‘encouraged’, from all available sources, including private sector loans etc. Even a note inserted to prevent use of the new NCQC fund for investment in fossil fuels was removed in an ultimate irony for a new climate fund! The difficulty of passing any funding obligation at state level through the US Congress was the reason for the poor show. But that being the case, the question arises; why did they not just sidestep the US altogether which would never contribute?

Other damp squibs

Deadlocks similarly met attempts for substantive measures connected to the Mitigation Work Programme where again any reference to the stocktake or national pledges was opposed setting the tone and signal for weaker commitments in those pledges when they are due over the next year in time for the COP30 and ten year anniversary of the Paris Agreement to be held in the heart of the Amazon Forest in Brazil. Not a good omen!

Similarly, only minor commitments on Adaptation, Loss and Damage funding, where ethe UN secretary general viewed as a ‘wrong inflicted on the vulnerable’ Even the outcome on the Just Transition Work Programme (JTWP) intended to assist fossil fuel dependent countries to transition to clean sources was described as a betrayal. No new commitments on deforestation or food and water either.

The low levels of commitment at COP29 was characterised by the failure of several major leaders to attend, including from China, India, France Canada, Brazil and Australia but most of all from the United States, with the election of Trump who promises casting a dark shadow indeed over the event.

Glimmers of Hope

A notable exception to the gloom was the agreement of the final elements to make Article 6 of the Paris Agreement operational facilitating a key global mechanism for the funding of carbon removals through a marketplace.

The Article 6 rules firm up the process for ensuring transparency and additionality and permanence to carbon credits bought and sold and potentially facilitating a major source of new funding to the developing world and a system that had previously had fallen into discredit. The EU, long a leader at COPs for climate action, official view was that the climate financing agreed was the best outcome that could be achieved in advance of a Trump election. The EU signalled, along with China and the UK, to take up leadership in the expected absence of the US following Trump’s inauguration in January 2025.

Conclusion

With bleak prospects, it is not surprising maybe that the commitments were so small. But that countries were willing to continue to negotiate in good faith with the uncertainty of the Trump election was claimed as a success as showing the resilience of the COP process. Slim pickings indeed. Unfortunately the science and the climate is oblivious to such nuances of achievement.

But the main hope must nevertheless be that the transition to renewable energy as envisaged in the most recent IEA World Energy Outlook 2024 also proves to be resilient to these political changes. The hope that the economic argument for renewables can beat the entrenched ideological commitments to fossils; assumes a level playing field of competition which is not guaranteed at all.

It is also however very possible that with the increasing damage and cost of climate change; people will start to see and support the logic of the transition away from fossil fuels to clean sources of energy. That recognition of the destruction caused by climate events beginning to be experienced more and more intensely and frequently now is an important and perhaps the most critical factor favouring the transition, but at what cost remains to be seen.