Context – Climate Change Impacts – Forests and Biodiversity

Contents:

- Introduction

- Climate Change Impacts – Forests

- Climate Change Impacts – Biodiversity

- Recent News – Links

1. Introduction –

The purpose of this Context article is to provide a basic explainer of the climate change impacts on weather and weather extremes. The Article utilises key selected extracts from reputable sources as well as from UNFCCC’s most recent benchmark IPCC’s 6th Assessment Report, Working Group 1 – Climate Change 2011: the Physical Science Basis (6thAR-WG1) which are all fully referenced at the start of the extract – direct extracts are copied in italics and highlighted in maroon for emphasis.

The aim is to set out in summary, the climate change drivers as well as the effects and impacts on land and food currently experienced as well as the likely committed changes and possible future consequences, depending on the climate change pathway into the future.

This future pathway is itself dependent on the global Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions trajectory particularly from Carbon Dioxide (CO2) and Methane (CH4) and whether these continue to increase, level off or are reduced and at what speed committing the world to warming of 2.7 degrees on current trajectories as outlined in this article or other outcomes; what happens is essentially in our hands.

At the end a number of the article a number of links to recent articles are listed which provides further information and evidence of the impacts, this list will be updated from time to time to keep current. A basic outline of greenhouse gases, emissions and temperature rise is provided in the short Impacts – Introduction Context article

2. Climate Change Impacts – Forests

Extract from Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations(FAO) – The state of the Worlds Forests, 2020 State of the World’s Forests 2020:

Forest ecosystems are a critical component of the world’s biodiversity as many forests are more biodiverse than other ecosystems.

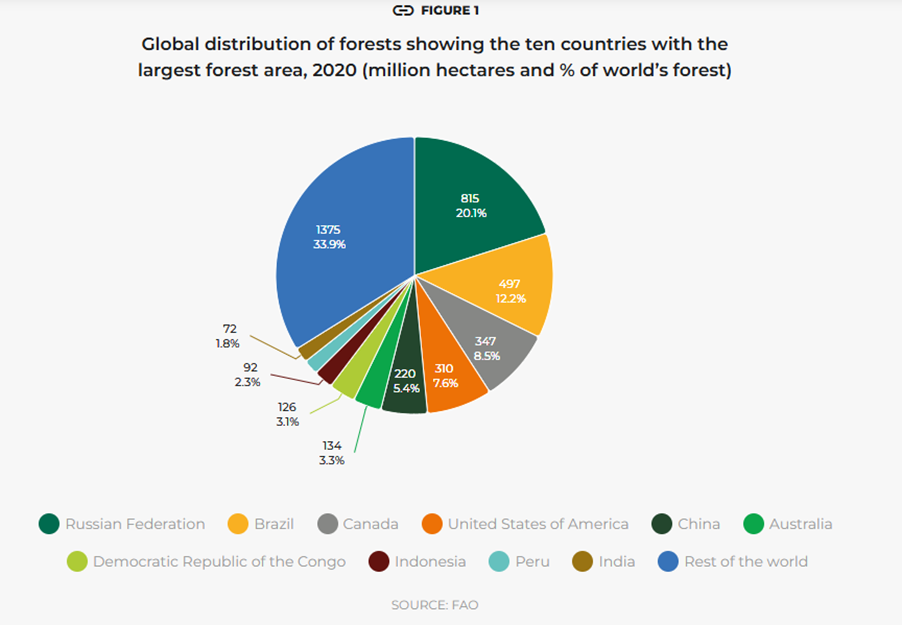

Forests cover 31 percent of the global land area. Approximately half the forest area is relatively intact, and more than one-third is primary forest (i.e. naturally regenerated forests of native species, where there are no visible indications of human activities and the ecological processes are not significantly disturbed)..

The total forest area is 4.06 billion hectares, or approximately 5 000m2 (or 50 x 100m) per person, but forests are not equally distributed around the globe.

More than half of the world’s forests are found in only five countries (the Russian Federation, Brazil, Canada, the United States of America and China) and two-thirds (66 percent) of forests are found in ten countries.

Deforestation and forest degradation continue to take place at alarming rates, which contributes significantly to the ongoing loss of biodiversity.

Since 1990, it is estimated that 420 million hectares of forest have been lost through conversion to other land uses, although the rate of deforestation has decreased over the past three decades.

Between 2015 and 2020, the rate of deforestation was estimated at 10 million hectares per year, down from 16 million hectares per year in the 1990s. The area of primary forest worldwide has decreased by over 80 million hectares since 1990.

Agricultural expansion continues to be the main driver of deforestation and forest degradation and the associated loss of forest biodiversity. Large-scale commercial agriculture (primarily cattle ranching and cultivation of soya bean and oil palm) accounted for 40 percent of tropical deforestation between 2000 and 2010, and local subsistence agriculture for another 33 percent.

Extract from UN Environment Programme – REDD+ REDD+ | UNEP – UN Environment Programme

Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation

Forests are an available, effective and cost-efficient key nature-based solution that can provide up to a third of the mitigation required to keep global warming well below 2°C. Forests have a mitigation potential of over 5 GtCO2e per year by halting forest loss and degradation, and sustainable forest management, conservation and restoration (REDD+).

REDD+ is a climate change mitigation solution developed by Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Its framework, the so-called Warsaw Framework was adopted in 2013 at COP 19 in Warsaw and provides the methodological and financing guidance for the implementation of REDD+ activities.

The Paris Climate Agreement recognizes REDD+ and the central role of forests in Article 5.

REDD+ reduces deforestation through the conservation and sustainable management of forests and supporting developing countries in turning their political commitments, as represented in their Nationally Determined Contributions, into action on the ground.

Forests mitigate climate change because of their capacity to remove carbon from the atmosphere and to store it in biomass and soils. When forests are cleared or degraded, they can become a source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by releasing that stored carbon. It is estimated that globally, deforestation and forest degradation account for around 11 percent of CO2 emissions.

Key facts

- During 2015–2020, the rate of deforestation was estimated at 10 million hectares per year.

- Currently 11% of all carbon emissions stem from deforestation – more than emissions from all means of transport combined.

- Limiting climate change to well below 2C cannot be achieved without REDD+.

- Halting deforestation and forest degradation can avoid emissions of more than 5 gigatons CO2e/year.

- Forest conservation and restoration can provide more than one quarter of the emissions reductions needed in the next two decades.

- The goals of the Paris Agreement cannot be met without the world’s forests: their mitigation potential by 2030 is about 5 gigatons/year, on par with that of industry and only behind the energy sector.

- Forests, however, are more than that. Protecting the world’s forests is crucial to meet the Sustainable Development Goals: they provide an array of critically important ecosystem services including habitat for biodiversity of global significance and livelihoods for vulnerable and indigenous communities.

- Forests and woodlands are important stores of planet-warming carbon dioxide, soaking up 30 per cent of emissions from industry and fossil fuels. But every year, the world loses 10 million hectares of forests, an area larger than Portugal.

- Deforestation and forest degradation account for approximately 11 percent of carbon emissions. If deforestation were a country, it would rank third in carbon dioxide emissions behind China and the United States of America.

3.Climate Change Impacts – Biodiversity

Extracts from UN: Biodiversity – our strongest natural defense against climate change | United Nations:

Biological diversity — or biodiversity — is the variety of life on Earth, in all its forms, from genes and bacteria to entire ecosystems such as forests or coral reefs. The biodiversity we see today is the result of 4.5 billion years of evolution, increasingly influenced by humans.

Biodiversity forms the web of life that we depend on for so many things – food, water, medicine, a stable climate, economic growth, among others. Over half of global GDP is dependent on nature. More than 1 billion people rely on forests for their livelihoods. And land and the ocean absorb more than half of all carbon emissions.

But nature is in crisis. Up to one million species are threatened with extinction, many within decades. Irreplaceable ecosystems like parts of the Amazon rainforest are turning from carbon sinks into carbon sources due to deforestation. And 85 per cent of wetlands, such as salt marshes and mangrove swamps which absorb large amounts of carbon, have disappeared.

How is climate change affecting biodiversity?

The main driver of biodiversity loss remains humans’ use of land – primarily for food production. Human activity has already altered over 70 per cent of all ice-free land. When land is converted for agriculture, some animal and plant species may lose their habitat and face extinction.

But climate change is playing an increasingly important role in the decline of biodiversity. Climate change has altered marine, terrestrial, and freshwater ecosystems around the world. It has caused the loss of local species, increased diseases, and driven mass mortality of plants and animals, resulting in the first climate-driven extinctions.

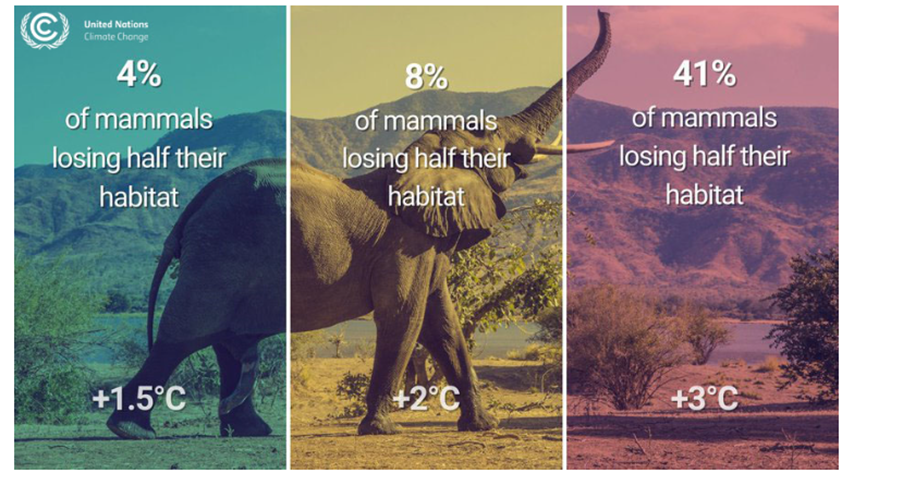

On land, higher temperatures have forced animals and plants to move to higher elevations or higher latitudes, many moving towards the Earth’s poles, with far-reaching consequences for ecosystems. The risk of species extinction increases with every degree of warming.

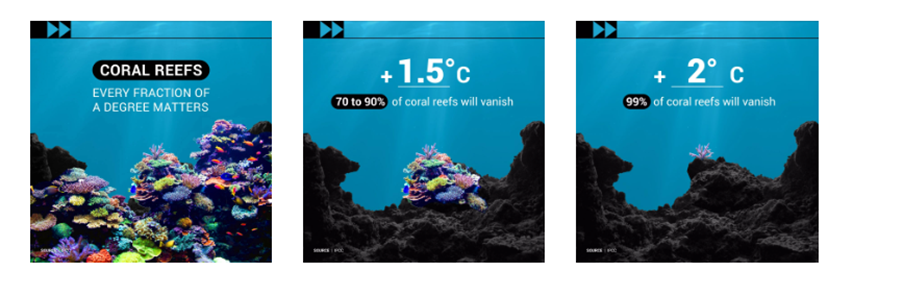

In the ocean, rising temperatures increase the risk of irreversible loss of marine and coastal ecosystems. Live coral reefs, for instance, have nearly halved in the past 150 years, and further warming threatens to destroy almost all remaining reefs.

Why is biodiversity essential for limiting climate change?

When human activities produce greenhouse gases, around half of the emissions remain in the atmosphere, while the other half is absorbed by the land and ocean. These ecosystems – and the biodiversity they contain – are natural carbon sinks, providing so-called nature-based solutions to climate change.

Protecting, managing, and restoring forests, for example, offers roughly two-thirds of the total mitigation potential of all nature-based solutions. Despite massive and ongoing losses, forests still cover more than 30 per cent of the planet’s land.

Peatlands – wetlands such as marshes and swamps – cover only 3 per cent of the world’s land, but they store twice as much carbon as all the forests. Preserving and restoring peatlands means keeping them wet so the carbon doesn’t oxidize and float off into the atmosphere.

Ocean habitats such as seagrasses and mangroves can also sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere at rates up to four times higher than terrestrial forests can. Their ability to capture and store carbon make mangroves highly valuable in the fight against climate change.

Conserving and restoring natural spaces, both on land and in the water, is essential for limiting carbon emissions and adapting to an already changing climate. About one-third of the greenhouse gas emissions reductions needed in the next decade could be achieved by improving nature’s ability to absorb emissions.

Is the UN tackling climate and biodiversity together?

Climate change and biodiversity loss (as well as pollution) are part of an interlinked triple planetary crisis the world is facing today. They need to be tackled together if we are to advance the Sustainable Development Goals and secure a viable future on this planet.

Governments deal with climate change and biodiversity through two different international agreements – the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), both established at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit.

Similar to the historic Paris Agreement made in 2015 under the UNFCCC, parties to the Biodiversity Convention in December 2022 adopted an agreement for nature, known as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which succeeds the Aichi Biodiversity Targets adopted in 2010.

The framework includes wide-ranging steps to tackle the causes of biodiversity loss worldwide, including climate change and pollution.

“An ambitious and effective post-2020 global biodiversity framework, with clear targets and benchmarks, can put nature and people back on track,” the UN Secretary-General said, adding that, “this framework should work in synergy with the Paris Agreement on climate change and other multilateral agreements on forests, desertification and oceans.”

In December 2022, governments met in Montreal, Canada to agree on the new framework to secure an ambitious and transformative global plan to set humanity on a path to living in harmony with nature.

“Delivering on the framework will contribute to the climate agenda, while full delivery of the Paris Agreement is needed to allow the framework to succeed,” said Inger Andersen, the head of the UN Environment Programme. “We can’t work in isolation if we are to end the triple planetary crises.”

Extracts from Effects of Climate Change on Ecology | Center for Science Education:

Effects of Climate Change on Ecology

Our climate is warming, which is changing the physical environments that support living systems. In the ocean, water temperatures are rising and becoming more acidic. On land, temperatures are rising as well, and soil health and freshwater quality are declining. In many places, environments are changing so fast that plants and animals cannot keep up, endangering entire ecosystems….

Slight changes in temperature are enough to cause spring thaw to happen earlier and fall frost to come sooner, which changes the timing of the growing season for plants and trees. This changes the availability of food, which can affect the size and health of populations within an ecosystem.

Rising temperatures threaten species diversity.

As temperatures continue to rise, many species are no longer able to thrive in places where they once lived. Scientists estimate that 8% of current animal species are at risk of extinction due to climate change alone.

Near the equator, a region with Earth’s highest biodiversity, many species are not able to adapt to rising temperatures. Reef fish are already living in the warmest water that they can tolerate and cannot survive as the water warms even more. It is also estimated that by 2070 nearly 20% of tropical plant species will be unable to germinate because of temperatures beyond their upper limit.

The frequency of hot, dry conditions increases as the climate warms, which intensifies wildfires. In the western United States, projections show that a 1°C rise in global temperature increases the average area burned by wildfires each season by 600%, impacting local populations of plants and animals in the path of the fires. The bushfire that burned over 25 million acres in Australia during 2019-2020, which started due to a lightning strike following an especially hot, dry spell, killed an estimated one billion animals. Many of the animals that died in these fires are found only in Australia, which raises concern about the future of these unique ecosystems. While local plant and animal populations usually recover following a fire, species that only exist in very small numbers or are found only in limited places are at higher risk for global extinction.

Sea level rise is causing the loss of coastal ecosystems.

Rising seas are displacing hundreds of thousands of people along the coasts and causing the loss of wetland ecosystems. By 2080 as much as 22% of the planet’s wetlands could be lost due to sea level rise. Coastal Louisiana, US, which has over two million acres of wetlands, is losing about a football field worth of land every 45 minutes, which is faster than almost any other place on Earth. Wetlands ecosystems protect coastlines from floods and store three times as much carbon as forests, which is important for mitigating climate change. The loss of coastal wetlands due to climate change threatens the diverse species of plants and animals that live within them, and impacts fishing economies that depend on marine life.

Coral reefs are dying due to warming ocean temperatures.

Healthy coral in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef are brown and green, while bleached coral that have been damaged due to warming ocean temperatures are white. Credit: NOAA

Studies estimate that one third to one half of the Earth’s corals have been lost, due in part to the warming ocean. When average ocean temperatures rise just 1°C, the coral become stressed and expel the symbiotic algae that make their food, resulting in the appearance of white coral (called coral bleaching). Though coral reefs cover less than one percent of the ocean floor, they support about 25% of all life in the ocean. The loss of coral reefs threatens marine ecosystems that depend on reefs as nurseries for fish and other marine species. Coastlines normally protected by coral reefs are also more vulnerable to erosion and storms.

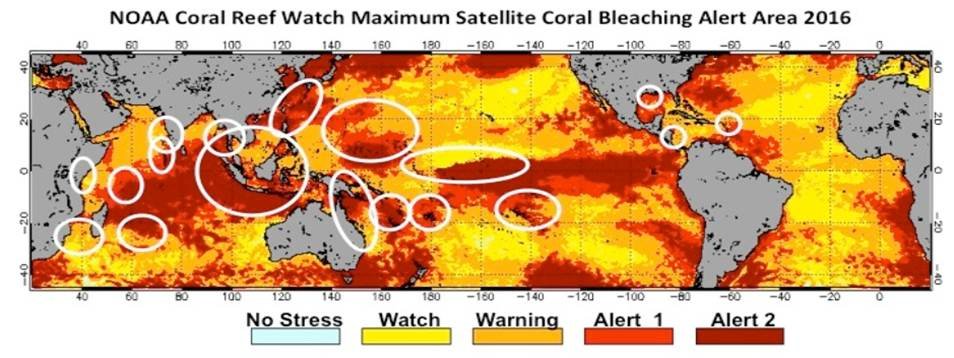

In this Coral Reef Watch Alert Area map for January-December 2016, severe bleaching was reported in areas circled in white. Note that there aren’t any coral reefs in the “No Stress” category, a sign that warming temperatures due to climate change are endangering coral reefs on a global scale.

NOAA

MCL – April 2025 (next update schedule: Spring 2028; more regular updates in the ‘Recent News Section’below).

4. Recent News – Links

Climate Junction Posts –

Other News Links –

Forests –

- Study: Wildfires will make the land absorb much less carbon, even if warming is kept below 1.5°C (phys.org) They found the global warming level at which fire began to impact the land’s ability to absorb carbon was 1.07°C above pre-industrial levels, and that fire is already paying a major role in hampering that ability. The findings are published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

- From Bolivia to Indonesia, deforestation continues apace (phys.org) Forests nearly the size of Ireland were lost in 2023, according to two dozen research organizations, NGOs and advocacy groups, with 6.37 million hectares (15.7 million acres) of trees felled and burned. – ‘backsliding – [how far do we have to fall before we see it is our interests – very far if you consider Florida hurricane hits – when we do, will it really be too late and our focus shifted to slaughtering each other in this developing dystopia?] Move away from tree felling – but trees elsewhere are held up as the sustainable future for building!! PHOTO

Biodiversity –

- Corals are starting to bleach as global ocean temperatures hit record highs – The Conversation – July 2023