Accelerating Danger – Part 3: What Faster Heating Means

Introduction

If the climate system is more sensitive to greenhouse gases than models have assumed, the consequences are serious, even stark: shrinking carbon budgets, shorter timelines, and a greater risk of crossing dangerous tipping points. From collapsing ice sheets to potential disruption of the Atlantic Ocean’s currents, accelerated warming forces us to confront what kind of future we are heading toward and faster than we previously thought.

Remaining Carbon Budgets and shorter timeframes – the clock is ticking faster

The 2024 annual climate condition update report, prepared by Piers Forster and other prominent climate scientists takes account of the continuing reduction in sulphate aerosols in the atmosphere through effective environmental policy measures. These aerosol cause local air pollution but also have the significant side effect, of reflecting heat back out to space. The reduction of these aerosol pollutants is also beginning to reveal the full heating effect of greenhouse gases which had been previously masked by their presence in the atmosphere, as we saw in the second article in this series. Because of the reduction of these aerosol a clearer understanding of this masking effect is emerging. The 2024 Update Report has for this reason cut the carbon budget estimate to remain within relatively safe warming limits by approximately 100 giga (billion) tonnes of Carbon Dioxide (100GtCO2).

Furthermore because of this adjustment, the Report indicates an upward revised global average heating value of + 0.45 degrees Celsius per 1,000GtCO2e emitted ( referred to as the ‘Transient Climate Response or TCRE).

To date the global climate has heated by an average of 1.24 degrees Celsius (conservative assumptions) since the start of the industrial age. The Forster Update report estimates that based on these adjustments only 130 GtCO2 now remains in our ‘carbon budget’ for a 50: 50 chance of keeping below the headline 1.5C average global warming rate(with some considering that we have already breached this threshold as we saw in Part 1 of Accelerating Heating series); 490 GtCO2 for 1.7C warming and 1050 GtCO2 to remain below the 2C warming threshold, considered the upper heating boundary for ‘safer’ climate warming conditions under the Paris Agreement.

Given that total human related emissions is indicated at 53.6 GtCO2 per year (including land use change and methane emissions) this would mean that there remains less than 3 years to utilise the remaining carbon budget for 1.5 degrees; less than 10 years for 1.7 degrees and less than 20 years for the 2 degree warming thresholds to be breached.

This adjustment is of upmost significance to our understanding of the climate system. Forster’s 2024 update report goes onto to outline the impacts of what breaching these thresholds means for our planet in the near future but with extremes of drought, heatwaves, storms, rainfall and flooding even now starting to become more apparent in our daily lives.

What does higher Climate Sensitivity actually mean for us?

While the 2024 Annual Update Report takes into account the accelerated heating impact of reduced aerosol and cloud reflectivity, what the report doesn’t do is to proceed to calculate the increased sensitivity of the climate system.

It is a crucial metric because it a measurement of how sensitive the Earth is in its heating response to a given volume of CO2 held in the atmosphere; providing a key measure for predicting future climate change.

Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity (ECS) is defined as: the measure of how much the Earths global average temperature will eventually increase for a doubling of CO2 concentrations from pre-industrial levels.

The latest IPCC 6th Assessment Report in 2021 put ECS at between 2.5 and 4 degrees in the most likely range and between 2 and 5 degrees in the outer bounds range being the likely amount of global average heating for a doubling of CO2 compared to pre-industrial times.

In James Hansen’s 2023 paper, Global Warming in the Pipeline (referred to by former UK Chief Scientist, Sir David King as one of the most important in years), Hansen calculates ECS at 4.8 degrees Celsius. As can be seen that is near that outer bound of the IPCC’s ECS widest range and much higher than the 3 degrees that has emerged as a common focus point of discussion .

That is a large difference of major consequence. The reasons for this higher ECS, as Hansen indicates, include the loss of aerosols and cloud reflectivity (as we looked at in Accelerating Danger, Part 2) as well as climate feedbacks.

Climate feedbacks are a particular concern as they contribute to increased earth system sensitivity as well as driving further deterioration of the climate system itself. Hansen in his 2024 article, Comments on Global Warming Acceleration, Sulfur Emissions, Observations, highlights in particular the risks to the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Current (AMOC) which provide among other benefits a temperate and mild British Isles [see AMOC context page here] and the real danger of passing a point of no return in the operation/overturning. He states:

If accelerated warming (Fig. 1) is not arrested, it will accelerate ice melt and freshwater injection onto the North Atlantic. Such increased freshwater injection, rising temperature of the ocean surface layer, and increased rainfall over the North Atlantic Ocean – all certain to occur if accelerated warming is allowed to continue – are the elements that are predicted to drive AMOC shutdown within 2 to 3 decades.

So the consequences of our delayed action are catching up with us, both in terms of immediate climatic consequences in the extremes of weather that we are beginning to experience more frequently but also in the shortening horizon for the occurrence of larger scale system changes in a heating world.

Plan B?

One obvious, but very controversial ‘fix’ for the reduction of aerosols as discussed in the previous article in this series (Unmasking the Drivers of Accelerated Heating) is their artificial replacement by a solar radiation management or geo-engineering technique of ‘Stratospheric Aerosol Injection’ (SAI) [see context page here]. SAI would again involve the launch of sulphur aerosols (tiny particles) but this time intentionally and high into the upper atmosphere where they do not cause air pollution in order to reset the earth energy imbalance by again reflecting back the ‘excess’ portion of incoming sunlight in a controlled manner. This has been characterized as truly another Faustian pact of major consequences; ‘playing God’ with the climate and with the potential for yet unknown impacts on our climate and weather systems.

The alternative of course is a rapid reduction in carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning but it is also probably correct to say that the longer that reduction in emissions is delayed, the more likely that there will be no alternative to the artificial introduction of some form of replacement aerosols as a short term measure to prevent the collapse of climate systems, at least as we know them today.

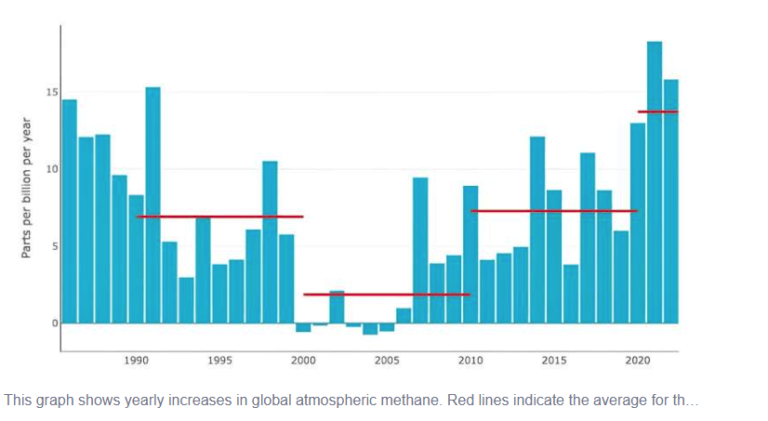

Nevertheless, as Foster and team states towards the end of their 2024 Annual Climate Condition Update, there are signs that something may be happening with our emissions. While CO2 emissions are at an all-time high, there is evidence that the rate of increase has slowed if not yet plateaued; if correct this would be the first faint indictor of some deacceleration in the warming climate system. While potentially very significant in itself, the pace would need to quicken and rapidly begin actual global emissions decline not merely a slowing increase.

Accelerating Danger Series – Conclusion

The climate sensitivity of this beautiful planet to our carbon emissions has been more revealed perhaps more than ever before by the trail of articles from Hausfather through Hansen’s work to Forster’s update report as explored in this series of Accelerating Danger, and we have less time than we ever thought previously. But the small, recent deceleration shows that change is possible. Understanding what this means in terms of what specifically we need to do in the more limited time now available to available would be a very good place to start.

The science is sharpening, the warnings are louder, and the time horizons are shorter. Yet there are signs — faint but real — that emissions growth is slowing. The question now is not whether change is possible, but whether we will move fast enough to match the speed of a heating world.

MCL – September 2025